Lao Zheng Xing (老正兴菜馆) — Traditional cuisine in Shanghai, with a Michelin star to go with it.

Shanghai is probably the most accessible Chinese city for foreigners.

Once a small fishing village, the city underwent a sudden period of rapid growth and transformation starting in the mid-19th century. It was turned into an international port, and foreigners from various countries established concessions within the city. The British and French concessions played a particularly big role in shaping Shanghai’s architecture, economy, and social norms. This era, marked by a blend of Eastern traditions and Western influences, laid the foundation for the city’s future rise as a global metropolis.

During the 1920s, Shanghai’s Golden Age was characterised by rapid modernisation, economic growth, and a vibrant arts and entertainment scene. Shanghai became a hub for intellectuals, artists, and writers, who established themselves in the city, attracted by the vibrant lifestyle. The Bund’s architecture, from the Peace Hotel’s Art Deco to the neoclassical Custom House, is a monumental example of the grandeur of that era.

The Western bank of the Huangpu river: Shanghai HSBC Building and Customs House on the Bund.

Right across the water, LEDs and skyscrapers are a symbol of Shanghai in the 21st century.

On the opposite bank of the Huangpu River and in stark contrast to the Bund’s 20th-century palaces and warm incandescent lights, stands Lujiazu, the aggressively modern financial district with its unmistakable skyline and LED-clad skyscrapers. The new spurt of development came after a period of economic stagnation following 1949. The city experienced a remarkable resurgence in the early 1990s, fueled by China's economic reforms and new policies that opened up the city to the world, leading to an economic boom that transformed Shanghai into a thriving metropolis.

Central Shanghai embodies China's rapid process of modernisation and globalisation - old and new, traditional and contemporary, with a thriving economy that’s turned the city into a magnet for both domestic and international visitors.

Not just crab invasions:

Shanghainese cuisine.

The large influxes from other countries during the booming years of the city had an influence on the culinary scene as well. Haipai cuisine is the result of food traditions and cooking methods from around the world clashing, mingling and coming together while adapting to the locals’ taste in the 20th century.

Before that, and going back to the Ming and Qing dynasty, Benbang cuisine (本帮菜) was the staple in the region. Far from the flavour explosions of Sichuan and Hunan cuisine, Shanghainese food tends to focus on a more subtle flavour profile. Mellow and gentle, it strives to preserve the original flavours of the ingredients, it features soy sauce, rice wine and sugar as prominent seasonings. The sweet-and-sour combination is also typical of the region.

Before the city’s boom, the local cuisine focused on food that would give workers enough energy for the day, hence the reliance on sugar and soy sauce. Meat, fish and seafood were not everyday fare, but with the rise of the working class and improvements in the economic conditions in the area, those became far more common.

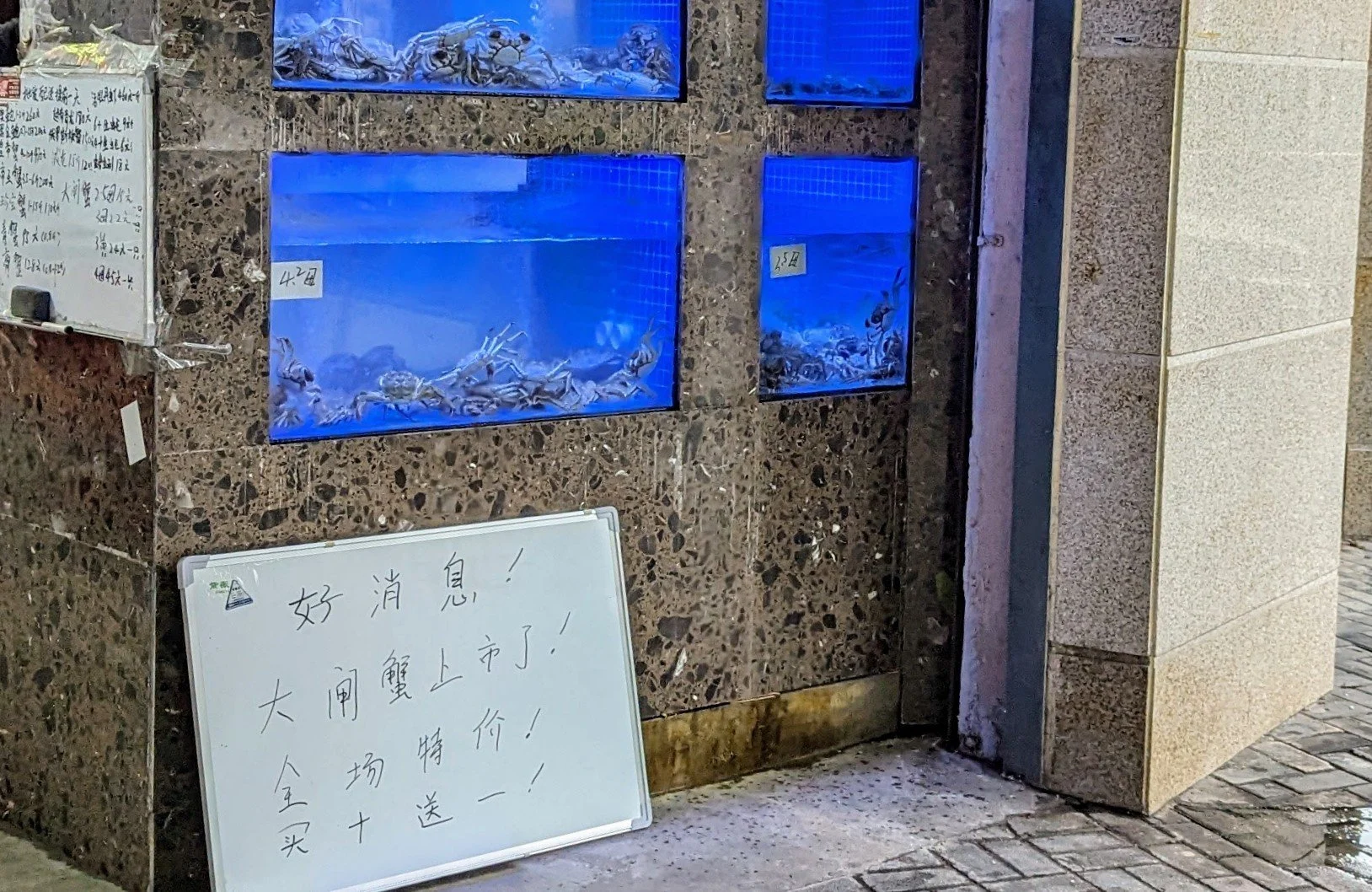

In autumn, for example, crabs take over the city. The hairy crab craze tends to last from the end of September until well into November, and during this time restaurants feature a variety of dishes and full menus centred entirely around the 10-legged sea bugs, their buttery roe and sweet meat.

Nowadays, the food scene in Shanghai offers pretty much all the variety one could dream of, but Benbang cuisine has been pushed to the side throughout the decades. Traditions are, however still being kept alive in home kitchens, and the local cuisine still goes strong in several restaurants in town - some of which even ended up getting the seal of approval from a certain well-known culinary guide.

Lao Zheng Xing: a Michelin-starred restaurant in Shanghai

with a history.

Shanghai’s rise as a hub for foreign workers and tourists meant that the options it offers in terms of food have grown to match its role on the international scene. It boasts some of the best fine dining and traditional restaurants in China, with more than 50 restaurants being awarded 1 or more Michelin stars since 2017, the year the first edition of the Shanghai Michelin Guide was launched.

The Michelin guide has a reputation for suggesting restaurants that serve exceptional food. While that’s true, the whole concept is usually linked to fine dining, and when you think of Michelin-starred fine dining you’re better off assuming it’ll come with refined service, extravagant ambience and a bill to match the experience. Stacking up against forward-thinking fine dining restaurants and impressive dining halls is a hard task, but Lao Zheng Xing is a bit different in that regard.

Michelin Star Plaques at Lao Zheng Xing, with their inconsistent logos and sequencing. Entertainingly chaotic.

Instead of competing on luxury, Lao Zheng Xing focuses on signature Shanghainese dishes and cooking methods, with carefully prepared food to preserve a tradition that’s no longer as ubiquitous as it might’ve been in the past.

Chopsticks and dinnerware are a run-of-the-mill affair, and if the tablecloths are a bit creased so be it.

In business since 1862, the current location opened in 1997 in Huangpu, taking up a 6-story building. As soon as you step into the door, you’re met with an unassuming lobby leading to a lift that gets you to the upper floors and a pillar plastered in bright red plaques showcasing all the Michelin stars it’s been able to retain each year since 2017. Lao Zheng Xing’s rating was most recently confirmed in the newly released Michelin Guide Shanghai 2025, which awarded it one star.

Choices and more choices. The menu.

The menu is… vast, to say the least, and very Shanghainese.

They’re known for their local Shanghainese specialities and signature dishes, including fried river shrimp (I’ve seen heaps of them being served, a very affordable option for the portion size) and braised sea cucumber.

I went for a selection of local musts, skipping the shrimp and the sea cucumber, mostly getting dishes I knew I would not be able to get once I’d left Shanghai.

At the time of my visit in 2023, most of the mains came in at under 150RMB (20 USD), with some more labour-intensive options or sea cucumbers costing significantly more. It’s a budget-friendly option to experience elevated local cuisine in Shanghai, and an experience for someone who wants to tick off a starred restaurant without breaking the bank.

The Dinner Spread:

Not many vegetables but playing on hot and cold.

Drunken Chicken — 正兴醉鸡

Minimal.

Drunken chicken is a classic.

Very aptly named, it’s made by marinating poached chicken in huangjiu - yellow wine. The chicken is poached until tender, then sliced and served cold in its marinade. Subtle and springy, with sweet notes from the wine coming across beautifully and a refreshing mouthfeel.

Commonly served both as an appetizer and a standalone dish, it’s readily available even in Chinese restaurants abroad.

Lao Zheng Xing’s version did not disappoint.

Price: 56 RMB

Braised Pork belly with fermented tofu — 老正兴酱方

Over-the-top rich.

Lao Zheng Xing’s version of Dongpo pork.

A dainty cube of pork belly with plenty of layers of fat and meat, slowly braised and slathered in a sauce in which fermented tofu takes centre stage. Almost translucent, the consistency might be challenging if you’re not used to the gelatinous bites that are so common across Chinese cuisine. But if you are, giving it a try is worth it.

On the smaller side, but anything larger than this portion would be overwhelmingly fatty.

Price: 168 RMB

Shanghai Smoked Fish — 上海熏鱼

No smoking.

An instant favourite.

Despite the name, no smoking is involved. The smokiness comes from the soy sauce “glaze” the fried fish is tossed into, which includes dark soy sauce, vinegar and some sugar. Once the chunks of white fish are crispy - and I mean crispy, almost overcooked - they’re thrown into the glaze while still scorching hot, “smoking” the sauce and making it stick.

It’s then left to marinate and soak up the sauce, and served cold.

This results in firm fish bites with a charred look but only a slightly crisp exterior, that are pleasantly meaty and intensely umami.

Typically made with carp or pomfret, but any firm white fish with larger bones would probably do. I made it at home, compiling a couple of recipes from the web (see here), but the amount of frying involved and the lingering smell that permeated my kitchen for days means I’ll probably stick to ordering it in restaurants from now on. Too bad this dish doesn’t seem to be easy to find abroad.

Price: 52 RMB

Stewed silken tofu with crab roe — 蟹粉白玉

’twas the season.

Over-rice must when it’s crab season in Shanghai.

There’s no escaping it. Crab and crab roe pop up on every menu in town.

Soft and custardy tofu cubes in a bright yellow sauce that’s umami, thick and warming.

I wouldn’t say the stewed silken tofu with crab roe was the highlight of my meal, but it is the seasonal thing to get, and a solid rice-killer sauce to mix into a bowl of rice.

Price: 48 RMB

Scallion Pancakes — 葱油饼

Can’t say no.

An easy choice.

I’ve never passed on the chance to order a cong you bing, and the versions I tried in the Shanghai area were consistently flakier and crispier than the ones I had across Taiwan.

The three bite-sized scallion pancakes were crisp and flaky, not oily at all. They came on a frilly paper doily: the presentation couldn’t be further from what I’d expect from a starred restaurant, but it did add a bit of innocent charm.

Price: 24 RMB

Jellyfish head with cucumber — 黄瓜海蜇头

Shameless crunch.

Jellyfish bites layered on top of shredded cucumber, showered in Chinkiang vinegar, with a hint of sesame oil.

Served cold, shamelessly crisp and slippery. A well-needed acidic interlude alongside the rest of the dishes, and a great kick to balance the soothing drunken chicken.

Price: 68 RMB

Fried river eels —

响油鳝糊

Savoury and glossy.

Another typical dish from the local Shanghai and Suzhou cuisine, strips of freshwater eel, lacquered in a thick, sweet and savoury sauce with huangjiu, ginger, scallions, light and dark soy sauce and sugar. After stir-frying the eels and scattering some chives on top, hot oil is poured over the dish, releasing the aroma of the chives and leaving the filets slippery and glistening.

Price: 94 RMB

When in Shanghai…

To this day, Shanghai is a city most tourists travel through when in China, and it’s where most expats end up, making it one of the best places if you’re looking for variety on your plate.

But why settle for what you could easily find elsewhere? Lao Zheng Xing allows you to sample a vast array of local dishes and to cross a Michelin star off your bucket list while in Shanghai, in an unpretentious environment right downtown.

Well worth a visit — if you know what to expect.

Lao Zheng Xing Cai Guan (老正兴菜馆)

Shanghai, Huangpu, 福州路556号 邮政编码: 200002

On a calm side street in Ginza, Su is an intimate kushiage restaurant that specialises in gluten-free deep-fried skewers. With a focus on seasonal and local ingredients and attention to dietary restrictions, using rice flour and rice oil for frying, this small restaurant with only 6 seats is the perfect choice to try a Japanese staple if you’re gluten-intolerant or coeliac.