Travelling Taitung: Indigenous Cultures and Coastal Charm

The train ride from Taipei alone is worth coming down to Taitung.

Nestled along Taiwan's southeastern coast, Taitung County has established itself as one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country thanks to its lush green mountain ranges, a trademark of Taiwan’s natural scenery, and the wild beaches by the ocean that have been attracting surf enthusiasts for decades.

But once you get there you soon find out that there’s so much more to it than just surfing.

More than a surfer’s paradise.

In the past, the mountains and winding roads made the region harder to reach, which kept it from being the target of aggressive modernization programs and allowed for a lower flow of settlers and, in. recent years, tourists. Lately, efforts have been made to make Taitung more accessible as a tourist destination, turning its remoteness into an asset rather than a barrier to discovering its charms while striving to preserve its unique characteristics.

Sanxiantai Bridge. Photo by Arthur Tseng @arthur3607

You’ll find some of the best things to see and do in Taiwan: from the natural landscape, where the mountains meet the ocean, to vast rice fields stretching across the East Rift Valley, the outlying islands of Green Island and Orchid Island and scenic spots like Sanxiantai Bridge, with its 8 arches reaching out off the coast. But there’s more to discover than that.

There’s culture and traditions, and people who keep them alive.

Speed-Touring Taitung: 2 days in Taitung.

On my second week in Taitung during a short summer internship, I got to join a 2-day tour that would take me from indigenous villages that keep centuries-old traditions alive to a harbour town where Japanese colonial era influences are still clearly visible to this day, having become part of the locals’ everyday lives.

The tour was offered in English, giving me some much-needed support with the language and allowing me to get a condensed overview of what the coastal region has to offer early on in my stay.

Day 1:

Embracing Indigenous Traditions.

Taitung is home to 7 of the 16 indigenous tribes present in Taiwan, making it the most ethnically diverse region in the country, with indigenous people making up over 35% of the local population. Sheltered between mountain ranges and the ocean, the region was the last one to be colonised by Han Chinese in the late 1800s, and indigenous traditions and customs are prevalent in everyday life even today.

Between the city and the mountain.

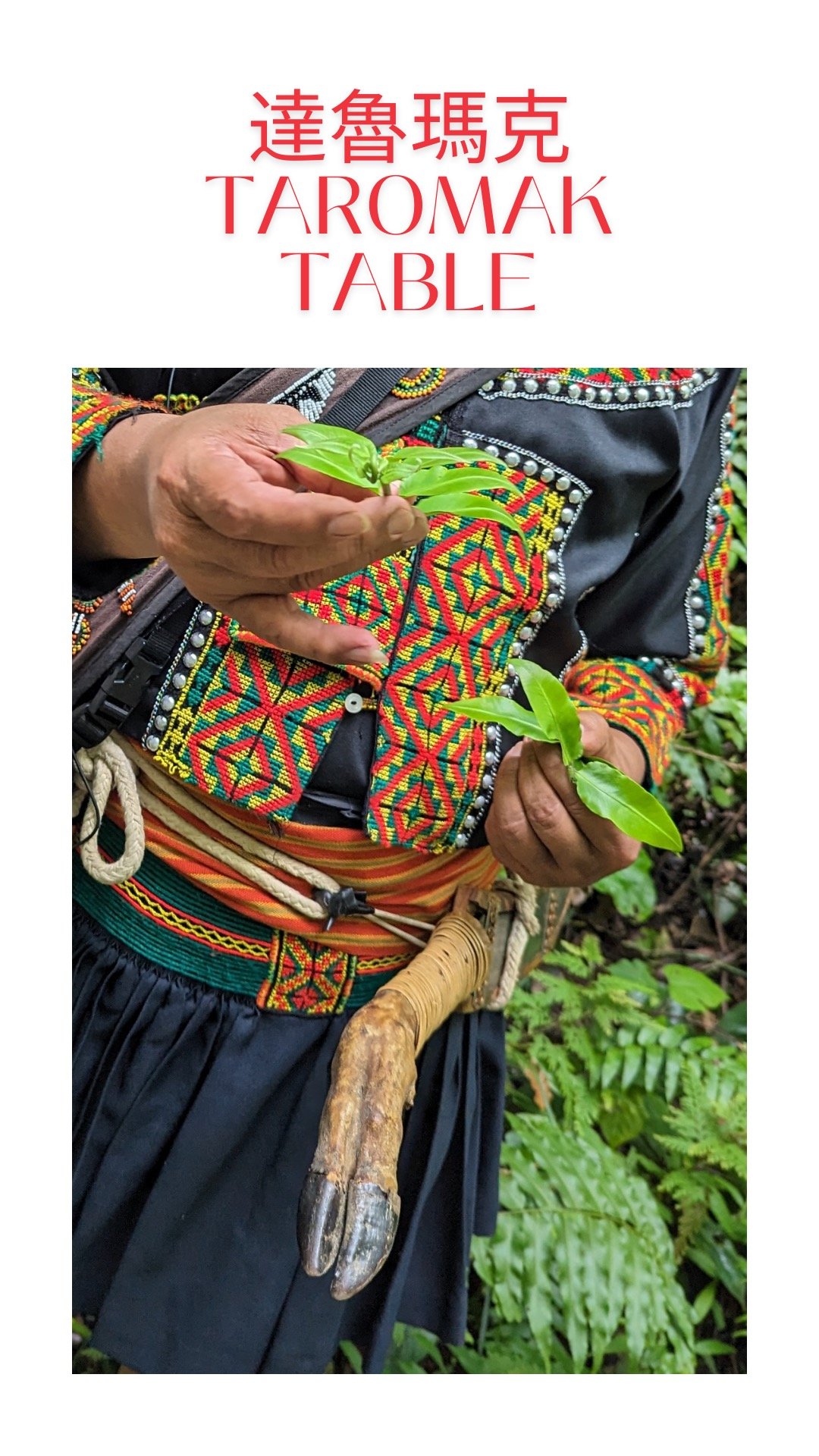

Just over 10 km from Taitung City, the first stop in our tour was at Taromak (達魯瑪克), the only tribe living within Taitung City.

After having been forced to move down from the mountains during the Japanese rule, the tribe settled around the village of Dongxing (東興), bringing their culture and customs with them. Annual rituals play a central role in the tribe’s life, with the millet harvest festival being a major event and the swing used as a bonding ritual between men and women that gets set up every year being the tallest in the country.

The connection to the land is still strong, with foraging up the mountainside playing a big role in the tribe’s everyday life and the preparation of traditional meals. Millet and betel nuts are used ritually as offerings for the ancestors, and the rich biodiversity in the field offers the locals anything from shrubs to be used as tools, to officinal herbs and small coffee plants growing next to century-old trees. Conscious consumption is at the base of all foraging and hunting in the tribe: you take what you need, no more. And on the way back down to the village you share what you have with the people you meet.

Heat. Steam. Smoke. The Taromak table.

Once back from a foraging trip on the mountain slopes, the meal we were treated to was wonderfully varied and a real experience.

Earth ovens are still used to make the most of the heat and coax the flavours out of simple ingredients, allowing one to cook multiple dishes at once, rendering mountain boar fat and having it drip down on vegetables arranged under the main protein source.

But it didn’t stop there. Grilled fish, blood sausage and abai (阿拜) are typical Taromak dishes. Blood sausages were a way for hunters to preserve meat during long hunting expeditions away from the village. Abai are millet dumplings with filling including anything from pork to shredded pumpkin, steamed for hours until soft and sticky. Similar to Chinese zongzi, they’re made with millet instead of glutinous rice and, on top of the tough shell ginger leaves used as the outer wrapping, abai have an inner apple-of-Peru (假酸漿) edible leaf layer that gives the dumpling a refreshing herbal aroma while, according to the locals, making them easier to digest at the same time.

Millet plays an important role in societies all over Southern Taiwan, and abai are not the only way the grain is used. Millet wine is home-brewed in most villages and in recent years, even millet donuts stalls have started popping up, frying up chewy treats with a satisfying bite, only slightly denser than your regular, run-of-the-mill wheat donut.

Life in the village - By the train tracks.

About a 40-minute drive south on the highway overlooking the Pacific, another tribal village is working to keep its heritage alive.

Duoliang (多良) is mostly known to tourists for having Taiwan’s most scenographic train station, situated on a stretch of railway running parallel to the coast just metres from the ocean. Population in the nearby village has been dwindling, and the lack of footfall meant passenger operations ended in the mid-2000s. The station has since been converted into a great spot for trainspotting with a view and opened to the public. Today, most visitors head there for a stop on their road trip and a photo op at the converted station.

The locals in the Calavi ( 查拉密) community, though, hope that the influx of visitors might attract some of those who moved out of the village to come back.

Driftwood and Coffee.

Following a typhoon and with plenty of high-quality driftwood having washed ashore on the nearby beach, a woodcrafting workshop has been set up in the hope of attracting young villagers back with the prospect of learning a new skill and putting them to good use.

A café also opened in the very heart of the village, bringing a modern approach to local ingredients and the Paiwan (排灣) indigenous products. 5181 聽海文創&咖啡 serves coffee grown in neighbouring Taimali (太麻里) and millet wine cocktails amongst other snacks and drinks, all of this while offering one of the best views on the East Coast.

Walking through the village with one of the young people that decided to come back to Duoliang made it possible to hear stories about local traditions and the community’s interaction with outsiders settling in, showing village dynamics that have evolved through generations.

The drive to develop woodworking and to offer guided tours of the village might just be the way to give the village another chance and bring it back to life.

A note on getting around Taitung.

While Taiwan’s east coast is more remote compared to pretty much any other of the country’s regions, Taitung is still well served when it comes to connections to the rest of the island. Taitung is easy to reach by car and served by its own airport flying to domestic destinations, but the most convenient option for tourists to get to the region is probably hopping on a train from any of the major cities.

The TRA (Taiwan Railways Administration) Taitung Line runs along the eastern coast of Taiwan, meandering through thick forests and peeking out onto the ocean, providing stunning scenic views along the journey.

Once you get to Taitung, though, venturing away from the train line can get trickier. Fortunately, plenty of scooter and car renting options are available, as well as a growing network of tours that cater for international tourists and expats living in the area, aiming to make it easier for them to reach even the most remote spots.

Useful links:

Visit the Hello! Taitung website at the link below to see all the activities they have available, including the Taromak Community and driftwood workshop in Duolian:

See the map below for the spots we visited in this tour, and click here for day 2 and the coastal life experience in Chenggong, from the harbour’s history to fishing boats and me chomping down on fish flesh.

Exploring Taitung has never been easier. Discover the rich traditions of the region, its history and the gastronomic events to showcase local products. Build your itinerary and choose to travel slow to appreciate all that Taitung has to offer.